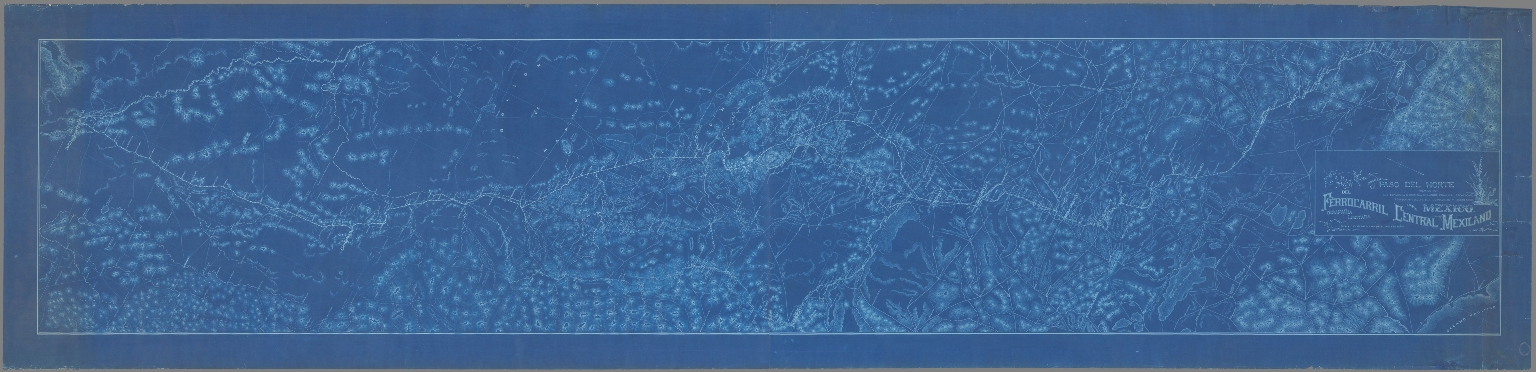

Date estimated., "A colossal (almost 3 metre / 10 foot long!) cyanotype (blueprint) engineers’ masterplan of the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano (Mexican Central Railway), the 1,969 kilometre-long railroad that connected Mexico City with El Paso, Texas, so creating the first great Mexican-American commercial-trading nexus, revolutionizing Mexico’s economy; the railways was by far and away the grandest project of ‘El porfiriato’ (1876 - 1911), the era of unprecedented political stability, economic growth, scientific progress, and booming infrastructure that Mexico experienced under the rule of the military strongman Porfirio Díaz Mori; the railway was owned by a Boston-based corporate syndicate and was built at lightning speed, between 1880 and 1884, by a team led by several of America’s greatest engineers; the unrecorded map, was seemingly executed in 1881, shortly after construction of the railway commenced, and was printed in Philadelphia by an architectural drafting shop in only a handful of examples to be used by the railway’s executive board, major investors and the engineering team as a vital strategic aid; it is seemingly the only surviving example of the largest, most detailed, and most beautifully composed cartographic record of Mexico’s principal railway, rendering it a critical original artefact from an endeavour that irrevocably linked the socio-economic destinies of Mexico and the Unites States. Prior to the 1870s, Mexico suffered from a severely underdeveloped economy with very little modern industry, terrible infrastructure, and communications systems, and grinding poverty, following decades of corruption, stagnation, internal instability, and foreign invasions that robbed the country of a third of her territory and much of her potential. This was even though Mexico boasted phenomenal natural resources wealth and human capital. Almost always, the best laid plans came to naught, a situation that frustrated the bright and ambitious figures in the Mexican elite. All this changed during ‘El porfiriato’, the 35-year long presidency of Porfirio Diaz Mori (1876 - 1911), which marked an era of unprecedented political stability, economic growth, and scientific progress. That being said, the Porfiriato, which collapsed into a decade of revolutionary turmoil, holds a controversial legacy, as it also saw profligate corruption, cronyism, political repression and rising income inequality. Diaz succeeded in rapidly modernizing Mexico, fostering industrialization, international trade and foreign investment, infrastructure programs, privatization, educational reforms, and advancements in science. His agenda was anchored in several mutually-dependent developments. First, was the privatization of vast amounts of federal land (new private land investment in Mexico grew from nearly nil in 1876 to £19.7 million in the 1910s). Second, was the professionalization and deployment of the armed forces to secure the countryside and the integrity of the republic’s borders. Third, were programs to improve land management, especially with respect to agriculture and forestry. Fourth, was fostering industrialization and mining (decade totals for mining grew from £1.3 million in 1880s to £11.6 million in the 1910s!). Fifth, was encouraging and managing urbanization, as Mexico was transformed from an overwhelmingly rural country into land of fast-growing cities. However, the critical element enabling all these advancements was the ‘Railway Boom’. During ‘El porfiriato’ the country’s railway network grew from only 640.5 km to 24,720 km, utterly transforming the country! Indeed, prior to Diaz’s administration, the only significant railway in the entire country was the British-backed Mexican Railway (Ferrocarril Mexicano), completed in 1873, that linked Mexico City to Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico. While the Ferrocarril Mexicano represented a great leap forward, what was really needed to jumpstart El porfiriato was a grand trunk line running up the spine of Mexico, from the capital to the U.S. border, connecting the country with its largest foreign inventor and trading partner, and integrating the soon-to-be burgeoning Mexican railway system with that of the U.S. Such a line could dramatically increase economic growth and lead the modern development of central and northern Mexico, especially one its intended spur lines were completed. Toward the end of the 1870s, the Diaz administration opened tenders for what would be one of the era’s most ambitious mega-projects. As with all the other major endeavours in Mexico during the era, it was automatically assumed that it would be spearheaded by foreigners, most likely Americans, as the immense costs and technical expertise far exceeded any domestic capabilities. By from 1876 to 1900, it is estimated that U.S. $500 million of American capital was invested in Mexico, of which 70% went into the railways. The bidding was won by an American syndicate led by the legendary banking and brokerage firm Kidder, Peabody & Co., which, on February 25, 1880, incorporated the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano Compania Limitada, charted in Boston, Massachusetts (the railway was to be run exclusively out of downtown Boston for the duration of its existence). The enterprise secured highly favourable terms from President Diaz, who wanted the railway built quickly and securely, regardless of the costs, extending U.S. $32.5 million in construction subsidies (then an astounding sum!), as well as tax breaks and military protection. Importantly, the railway to be by far and away the financially largest and technically most ambitious endeavour of El porfiriato. The railway’s board immediately proceeded to organize the construction of the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano (Mexican Central Railway), which was to run from Mexico City up to Paso del Norte (from 1888 called Ciudad Juarez), to connect with the U.S. railway system just across the Rio Bravo del Norte (Rio Grande) at El Paso, Texas. Shortly thereafter, the Compania purchased the rights to build major spur lines; one departing the main line from Aguascalientes, through San Luis Potosi, to come to the Gulf Coast at Tampico; and the other to depart for the main line at Irapuato to run to Guadalajara as then the Pacific at San Blas. However, the priority was to build the Mexico City-Paso del Norte trunk line. The Compania wisely recruited an all-star team of engineers to plan and construct the railway, that included some of America’s most seasoned veterans, plus some of the brightest and most innovative young minds in the field. The project was overseen by Rudolph Fink (1834 -1913), who served as the railway’s General Manager and Chief Engineer. A German immigrant, based in Memphis, Tennessee, he had already been responsible for building several of the key lines in the U.S. South and was a driven and uniquely skilled manager of men and logistics. Fink’s right-hand man was Arthur Mellen Wellington (1847 - 1895), the railway’s Assistant General Manager, was a hugely accomplished engineer, who had held senior roles in planning and building many of the great railway projects in the U.S. and Canada. He supervised much of the day-to-day construction of the line. He was well-known for his line “An engineer can do for a dollar what any fool can do for two”. The priority was to set the precise intended route of the railway, an exceedingly difficult task, as it was to run over hundreds of kms of mountains and deserts, while the proper land concessions, etc. needed to be arranged in advance of construction. This charge was assigned to the brilliant young American engineer and urban planner Frank Henry Olmstead (1858 - 1939), who despite his youth, already had valuable experience working in challenging environments in places such as Idaho and California, as well as being a professional cartographer and draftsman. He subsequently became well known for laying out the urban plans for the cities of Fullerton, California and Billings, Montana. An exciting and consequential addition to the team was the young Norwegian immigrant Olaf Hoff (1859 - 1924), who was nothing short of a genius when it came to designing bridges and tunnels. He served as the railway’s chief engineer of bridges, and as the chief locating engineer, placing him in charge of fine-tuning Olmstead’s plan for running the route – a tremendous level of responsibility for a man in his early 20s! Critical to the present map, Olmstead and Hoff were responsible for setting the course of the Mexican Central Railway as showcased here in grand scale. Last, but not least, the other principal of the engineering team was Charles Adelbert Morse (1859 – after 1929), a young man who would subsequently become one of America’s greatest railway builders; he served as the Ferrocarril’s chief division engineer. While none of these men are today household names, they all became legends in the field of railway engineering and played critical roles in allowing North America to enter the modern age. The main line of the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano, running from Mexico City to Paso del Norte (Ciudad Juarez), being 1,969 kilometres (1,224 miles) long, was constructed with stunningly rapid, even lightning speed, albeit with great skill and care, with the entire project completed in only in 3. years! This was a testament to Fink’s superlative organizational skills, the almost super-human abilities of the engineering team, and the lavish funding provided by both the Peabody, Kidder syndicate and the Diaz administration. Construction started from the south, in Mexico City, on September 25, 1880, and the line was opened to San Juan del Rio the following year, with the continuation northwards as far as Lagos finished by 1882. Meanwhile, in the north, the line was constructed from Paso del Norte to Chihuahua by the end of 1882. By December 31, 1883, the line in both the north and south had progressed such points that only a 153 km gap existed in the middle. This was soon bridged and the mainline was completed on March 22, 1884 and was opened for business on April 10 following. The completion of the main line of the Ferrocarril almost instantly had a revolutionary effect upon the Mexican economy and its trade and social interaction with the U.S., as it connected to the American rail system at El Paso, allowing smooth integration with the Southern Pacific Railroad, Texas and Pacific Railway, and Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. As such goods could now travel in a matter of days from the heart of Mexico to reach virtually anywhere in the continental U.S., voyages that previously took weeks or months. Countless Mexican-U.S. business deals that were traditionally impossible were now rendered extremely cost-effective and desirable. Moreover, passengers could travel from Mexico City to the U.S. border (and vice versa) in only 3 days, which ensured a massive rise in tourism and educational/social trips between the countries. The railway quickly turned an operating profit, much to the delight of the Peabody, Kidder syndicate, while the Diaz administration earned far more from the higher revenues due the great economic growth that the line created than it had dished out in subsidies, etc. (although Diaz and his cronies had embezzled much of these funds). As for the two main spur lines, they were, at least initially, built much more slowly than the main line, as the latter was the priority, at least until its completion in 1884. Regarding the Aguascalientes-San Luis Potosi-Tampico line, the two alternative routes for its course from Aguascalientes to San Luis Potosi were investigated in late 1881, with the northern course being chosen as the route. Construction was slow, with the line reaching San Luis Potosi in 1889, while it was finished to Tampico in April 1890. As for the intended Irapuato-Guadalajara-San Blas line, the planned route from Irapuato to Guadalajara was surveyed in 1882, although construction did not start until 1887, while it would be completed to Guadalajara in 1889. The planned extension to San Blas was cancelled, in favour of redirecting the Pacific terminus to Manzanillo. This line would not be completed until 1908. This colossal, almost luminous, blueprint map (almost 3 metres / 10 feet long!) is an original engineers’ ‘masterplan’ of the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano, seemingly executed in 1881, shortly after construction the railway was commenced. It is apparently the only known example by far and away the largest, most detailed, and most beautifully composed cartographic record of Mexico’s principal railway known to survive, rendering it a critical original artefact from El porfiriato’s grandest project, responsible for irrevocably linking the socio-economic deities of both Mexico and the Unites States. The map was printed in Philadelphia, seemingly by an architectural drafting shop, as the handstamp of ‘McCollin’s / Philadelphia’ is faintly impressed to the verso. The map would have been issued in only a handful of examples and would have been used by the directors and the railway’s major investors during strategy sessions and presentations and may have been permanently displayed on the railway headquarters’ walls. The beautiful decorative Victorian-style title cartouche suggests that the map was intended to be both attractive (fit for presentation to VIPs) and technically useful. Additionally, examples would have been dispatched to Mexico to be used by Fink’s engineering team as the authoritative general guide for construction planning. In brilliant blue tones, the map showcases the immense corridor of the Mexico City-El Paso corridor to the grand scale of 10 miles to 1 inch, showing the 1,969 kilometre-long planned route of the Ferrocarril (the bold tracked line) as designated by Frank Henry Olmstead and refined by Olaf Hoff. Orientated north-by-northeast, the map shows the envisioned route as departing of Mexico City, snaking out of the Valley of Mexico, and through the Sierra Nevada and then crossing the Mexican Plateau, before descending into the deserts of Chihuahua. The topography is very accurately portrayed, with the mountains expressed by hachures and all rivers, arroyos, playas, and lakes charted, while the road system is precisely delineated. This was an impressive feat, as during this time Mexico was very poorly mapped, as such the Ferrocarril’s engineers would have to quickly (but carefully) execute trigonometrical surveys of the route under incredibly difficult conditions (often in blazing heat or chilly spells, in a land frequented by banditos). In many cases, these were the first scientific surveys of the areas covered, and the engineers’ work would later be incorporated into the El porfiriato’s Carta de la Republica Mexicana project, that aimed to map systematically and scientifically all of Mexico’s territory, producing a map of 1,100 interconnecting sheets done to a uniform scale of 1:100,000 (the endeavour would only ever be partially completed). The map labels all the railway’s envisioned intended stations, emphasizing the major cities that it would serve, including Mexico City, Queretaro, Aguascalientes, Zacatecas, Fresnillo, Chihuahua and Paso del Norte (Ciudad Juarez). Importantly, the route shown on the map accords to what was eventually completed in 1884, although some additional stations would later be added, especially in the central stretch of the line, between Fresnillo and Lerdo. Additionally, one will notice the very short spur railway that runs off from the main line at Silao, running to Guanajuato. This line predates the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano and was bought by the Ferrocarril company in 1880. The map is not dated anywhere, although an analysis of its detail reveals it to have likely been made in 1881, not long after the commencement of construction in September 1880. First, while the map shows a mature, and finalized route for the main line, few of the eventual stations in the midsection, between Fresnillo and Lerdo, are filled in, as such details were not decided upon until 1882 or 1883. Second, the intended route of the important spur line between Aguascalientes and San Luis Potosi (what was to eventually continue to Tampico) has not been finalized on the map, which rather shows the two alternative proposed routes for the line in the form of competing bold-dashed lines, with one running to the south, and the other running to the north. In late 1881 or early 1882, the line’s final route (the northern option) was chosen; thus, the present map predates this decision. Third, on the map there is not sign whatsoever of the intended spur line that was to run from Irapuato to Guadalajara (and which was eventually be continued to the Pacific coast), which was surveyed in 1882, and thus, the map predates this endeavor. The map does not feature an imprint of any kind. However, the name of the printer is revealed by the handstamp of ‘McCollin’s / Philadelphia’ faintly impressed to the verso. The map was made through the cyanotype (blueprint) printing technique, which is sometimes referred to as a ‘sunprint’. This photographic printing process involved the use of two chemicals: ammonium iron (III) citrate and potassium ferricyanide. Invented in 1842 by the astronomer Sir John Herschel, the technique was favoured by engineers, as it produced technical diagrams of sharp contrast and clarity. It also had the advantage of being very low cost and easy to execute (by those properly trained). In the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, the technique gained wide popularity for architectural and engineering plans (i.e., ‘Blueprints’). This led it to be adapted to cartography, often to maps of a technical nature, such as urban models and plans for mines and infrastructure (notably railways). A limitation of the cyanotype medium is that it could yield only a very limited number of copies, such that virtually all cyanotype maps are today extremely rare. The present map is seemingly unrecorded and is quite likely the only surviving example. This is not surprising, as the map would have been made in only a handful of examples for high-level private use by the railway company’s directors in Boston and the senior engineering team in Mexico. While the map is printed on thick paper stock, its large size and the fact that it was intended for active use, would have ensured a very low survival rate due to natural wear and tear. The present example thus comes down to us in remarkably good condition for a map of its genre. Over the coming years the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano continued to expand, building or purchasing new lines, to remain the dominant railway in Mexico and the country’s premier main nexus to the United States. It made ever greater profits, so much so that in 1906, President Diaz, wanted a bigger piece of the action, so he pressured the Peabody, Kidder syndicate to relinquish control of the railway in return for bonds. In 1909, the railway was then merged into the new state-run body of the Ferrocarriles Nacionales de Mexico, which was jointly owned by the Mexican government and private investors. In 1937, all the railways in Mexico were nationalized by President Venustiano Carranza. The old lines of the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano continued to play a critical role in Mexico’s economy, although state ownership ensured that it was not managed with the vigour as it had been previously. The lines were re-privatized in the 1990, with most of the former Ferrocarril Central Mexicano network being acquired by the Ferromex firm, which operates them to the present day. " (Alexander Johnson and Dasa Pahor, 2023), Map seemingly unrecorded. Cf. (re: background:) Hector AGREDANO, ‘Rails to Revolution: Railroads, Railroad Workers and the Geographies of the Mexican Revolution’, Ph.D. Thesis, City University of New York (2019); FOREIGN OFFICE (GREAT BRITAIN), Diplomatic and Consular Reports, No. 116 (London, 1889), pp. 1-35; Sandra Kuntz Ficker, Empresa extranjera y mercado interno el Ferrocarril Central Mexicano, 1880-1907 (Mexico City, 1995); William Rodney LONG, Railways of Mexico (Washington, D.C., 1925), pp. 15-29; Railway World, 26th year, vol. 8, no. 1 (Philadelphia, 1882), pp. 567-568; Report of the International American Conference Relative to an Intercontinental Railway Line (Washington, D.C., 1890), pp. 90-93.